Charting a Path for US Material Progress after the China Shock

A nation’s competitiveness depends on the capacity of its industry to innovate and upgrade.

The first wave of blame fell on the hoarders. When the pandemic-related shortages started, it was obvious individuals were looking to profit. The longer the shortages happened, though, the more a creeping realization slipped in. Americans knew their stuff came from elsewhere, but only then did they realize how fragile that relationship can be.

For over a century, it had been obvious that economic theory that favored trade would make people’s lives better because it did dramatically improve most people’s lives. By 2020, there was a growing bipartisan consensus that the theory was incomplete. It never could have anticipated China, who was fast to dominate new industries and slow to embrace any sort of liberal reforms. To chart a path forward that reconciles the benefits of trade while recognizing the risks, let us revisit those theories and their assumptions.

There are two core theories of interest: comparative advantage and competitive advantage.

Comparative advantage is concerned with cost: does one firm have a cost advantage to make the same kind of thing? The theory has been revised several times, first focusing on relative labor costs but in modern times it focuses more on opportunity cost. I am not an economist, so I will do my best to summarize. In theory, a business will make more of a good which is relatively cheap for them to produce than another, because it represents a lower opportunity cost. The other goods can be obtained via trade.

Competitive advantage is concerned with overall performance: what business structure will maximize profits? In contrast to comparative advantage’s focus on the cost of similar goods, competitive advantage is all-encompassing, asking how to use every part of a company’s operation to outperform others, from research consortiums to design to distribution.

By 1990, US business executives and investors believed that manufacturing in the US represented a huge opportunity cost for their capital. Labor was much higher, and many regions had enacted strict regulations around what kind of manufacturing plants could be built there and how they could be run. Manufacturing was only 22.9% of US gross domestic product (GDP). Michael Porter would translate this competition from firms to nation-state in his essay and book, Competitive Advantage of Nations. He claims, “A nation’s competitiveness depends on the capacity of its industry to innovate and upgrade.” He puts this in contrast to prevailing wisdom, that “labor costs, interest rates, exchange rates, and economies of scale are the most potent determinants of competitiveness.” He emphasizes the dynamic nature of international competitiveness that must be earned “not just once, but continuously”.

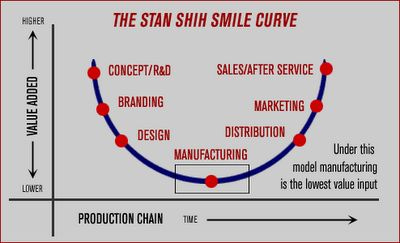

Yet the US abandoned trying to compete in all but the most advanced manufacturing industries like semiconductors, medical technology, and commercial airplanes. In a phenomenon dubbed the Smile Curve, manufacturing was considered to be the lowest value added activity compared to research, design, and marketing. This theory formalized a process that started in the 1970s in the US and concluded by 2010: the US will do R&D, the US will market their products, and the rest of the world can manufacture it. As a matter of course, the US expected that most basic manufacturing is interchangeable and competitive, such that US firms could find a supplier that would meet their schedule, quality, and cost needs. Every competitor had similar machines and materials, so the only advantage was in labor rate. As a result, manufacturing fled to countries with low labor costs and friendly attitudes towards manufacturing, starting with Mexico, Canada, and Japan. But China’s entrance was unique.

Per this story in the Wall Street Journal, after Mexico joined NAFTA, it took 12 years to double their imports as a percentage of US economic output. It took Japan just as long after they became a major US supplier in 1974. In a phenomenon dubbed the China Shock, China doubled their imports in just 4 years, precipitating the end of many US manufacturers. Those manufacturers found their customer base evaporating, who were drawn by China’s similar quality and dramatically lower prices. This sudden drop in revenue cut the timeline and resources available for US manufacturers to reinvent themselves. Chinese manufacturers were able to scale their exports so quickly thanks to massive incentives for regional governments to welcome manufacturing (what economists call foreign direct investment or FDI), lax environmental policies, and the allure for multinational manufacturers to increase their revenues by accessing the domestic Chinese market. China had a massive population, eager for the wages manufacturers could offer, and China accelerated that workforce’s development with more education. In return, the government demanded that foreign manufacturers share their technology via joint ventures. Foreign manufacturers found this a fair bargain, in many cases believing China would get the technology anyway, so they may as well make some money off it. As a result, from 1990 to 1994, China’s FDI grew from 1% of GDP to over 5% of GDP.

Over the next two decades, China would become home to the deepest pool of skilled manufacturing labor and effectively transition from being a low cost supplier to the best possible supplier for producing at scale. Americans benefited from cheaper goods, stock market returns from companies growing revenues in China, and nearly on-demand access to the latest, hottest technologies like new smartphone, TV, and laptop models. The relationship appeared completely mutually beneficial.

The economic theory took for granted the trust between two nations. In this case, the nations were organized extremely differently: the US, a democratic republic that operates on the timescale of elections, and China, a one-party, authoritarian nation. The absolute control of the Chinese economy was critical to fueling their ambition, putting total control of multiple industries in effectively one person’s hands. This structure is a known industrial end-point: a monopolizing trust. A trust’s playbook is straightforward: get the best technology by whatever means necessary, then scale output dramatically with low prices (below cost if you must) to drive competitors to forfeit or sell to you. When you are the only player left, raise profits and dictate the terms to everyone depending on you. Presently, there are fears China is pushing to monopolize more industries, as steel supply, solar supply, and EV supply are all far above demand. There are other plausible explanations than an attempt to destroy competitors: Chinese suppliers are incentivized by the state to keep producing, plausibly because their economy needs as much help as it can get. But regardless of motivation, the effect of their actions is to risk bankrupting competitors outside China lacking their government’s financial support. Those competitors are the best defense against China’s monopoly, though by now the range of goods they can address has narrowed substantially. The US has atrophied the muscles of building basic goods. Without those skills, it is more difficult to sustain a labor supply that can make the more advanced products that are important both economically and militarily. For example, chip manufacturers have experienced a shortage of skilled construction labor, and the US Navy has urgently run ad campaigns for workers to make new submarines.

These economic fears are compounded by national security fears. The most plausible fear is withholding: in a crisis, China would withhold critical goods necessary for the US to function. The other kind of fear is using their position as a supplier to stage a direct attack. This unique kind of fear was highlighted by the recent pager attack in Lebanon, when thousands of members of Hezbollah were wounded and killed as their pagers exploded after decades of terror attacks and outright war against Israel, serving as a worst-case example of a complete breakdown in trust and weaponizing the supply chain. That was with a relatively simple device, allegedly stuffed full of explosives. What more could be done if an entire network of drones or Chinese EVs were remotely controlled? Even without explosives planted, EVs are effectively a smartphone on wheels, with GPS, connectivity, and camera data that would be highly valuable for controlling and coercing a rival. The US is already racked with fears of surveillance from TikTok, who is legally obligated to share the information they access with the Chinese government. As China’s technical prowess grows, their products stoke more fear and face more threats of bans from the strained trust. These bans have precedent: networking equipment provided by Chinese manufacturers Huawei and ZTE were effectively banned because the manufacturers could not credibly demonstrate their trustworthiness and independence from the Chinese government. Continuing this trend, in September 2024 the White House proposed a ban on connected Chinese automotive components.

Re-industrializing the US requires a new economic theory that acknowledges and addresses these concerns. It must begin with a choice, the same choice Porter put forward in 1990: nations and their suppliers must choose to compete. Choosing to compete requires a change in thinking: manufacturing is not a low value activity to be outsourced but a dimension of competition to be improved and upgraded. That dictum holds true for both simple products and advanced manufacturing.

For basic goods, the only path for the US to build a durable comparative advantage is to build the most productive manufacturing ecosystem in the world given our higher labor costs, a good thing for a wealthy country. That means investing in our own highly skilled labor pool and augmenting it with the best manufacturing equipment in the world. This particular moment is a good one for investing deeply into productivity, as machine learning is powering impressive breakthroughs in image recognition for quality control, robotics, and other new kinds of automation. Similarly, the products the US manufactures must be internationally competitive. If what China is doing is actually selling below cost to drive out competitors, local manufacturers must find unique sources of profit to maintain their operations to sustain themselves until such a strategy becomes untenable.

For example, in the automotive realm, that means US truck sales are actually an effective hedge on Chinese monopoly. But EVs are the growth category in automotive, and China is building the world’s best EVs. Again, the US must choose to compete and hold themselves to the highest standard. The bar has been set, and American companies must meet or exceed that bar. The best way to do that is to let the consumer choose, and simply banning competition makes that impossible. Consumers outside the US will have a choice, though, which maintains some market dynamics. In 2023, 40% of Ford’s revenue came from outside the US, which is a strong incentive to compete.

If it is a severe national security threat, a ban is justified. A sufficiently high tariff may achieve the same effect as a ban, but why allow the threat at all with a tariff? A tariff is meant to protect local industry by making the imported product’s value proposition worse and generate tax revenue for the importing revenue. Neither of these addresses the actual problems: stopping a national security threat and making globally competitive products. A better solution would allow for a true market dynamic in the US by creating conditions that can mitigate the national security threats. Those solutions might include requiring American suppliers and data regulations that protect US consumers and national security. With the national security threat addressed, the next concern is that local manufacturing would be overwhelmed as other industries were in the first China shock. The best solution would enable them to move faster than China, a far cry from the status quo. If US manufacturers have four years to respond instead of 12 years, how expensive is a year of permitting review? (Note that projects using federal funds require a NEPA review, which averages 4.5 years.) Speed is essential to giving US manufacturing a fighting chance.

While that ideal solution may not be reachable, other options may facilitate competition while restricting China’s ability to overwhelm domestic manufacturers. One option borrows from China’s own restrictions on Western movies: limit the number of new models allowed to be sold. Eligibility could be restricted to prices that domestic manufacturers cannot or will not target to minimize the harm to consumers. For example, US manufacturers essentially do not have cars for under $20,000, so Chinese EVs priced under $20,000 would be eligible for sale. Similarly, supply limits could be put in place restricting sales. Consumers would bear the deadweight loss of restricted supply, but it would be less painful than the total deadweight loss of bans and extreme tariffs. Ultimately, there is no substitute for actual competition or moving quickly; the US desperately needs both. Wringing the cost out of their supply chain, moving quickly, and betting on machine innovation gives the US the best possible chance to compete and tip comparable advantage of even basic goods back in our favor.

By choosing to compete, seeing manufacturing as a source of competitive advantage, holding ourselves to the highest standards, and building a regulatory environment that mitigates security threats, the US economy can grow sustainably, recognize the benefits of international trade without fully protectionist measures, and have sufficient resilience to never face the pandemic-induced shortages again.

Thanks to Rob Tracinski, Emma McAleavy, Rosie Campbell, and Sean Fleming for help with this post.

Another way to counteract China's overproduction and price damping outside China is shifting the whole paradigm. Gen Z doesn't even want to own or drive a car. So, improving public transport infrastructure and making other tangential transportation services more advanced and accessible will shift transportation to another paradigm where there is just no need in so many privately owned vehicles—EVs or not. That's the way to deny the Chinese EV the market.