Material Progress Needs You

All we have to decide is what to do with the time that is given us.

Previously: Roots of Progress Fellowship, All Progress Goes Through Cost Accounting

The Wright Brothers did not need a permit to fly. Ford had an extremely basic permitting process to create the modern manufacturing line for automobiles. Western Union built the original telegraph network with a permitting system largely consisting of obtaining a franchise and right-of-way, which came largely from following the railways which streamlined negotiations with local municipalities.

Most material American progress occurred with limited friction, certain that projects could move forward in a predictable, fair way. Too much friction is actively strangling progress.

Unfortunately, friction is now everywhere, across all American industries. One recent case occurred as the US frantically builds semiconductor chip fabs. Completing these projects is considered a matter of national security and so important both political parties agreed to subsidize it. The fabs could be built faster if they could forgo an environmental review stipulated by the National Environmental Protection Act (NEPA). The party typically against environmental review argued that, if everything else has to go through with this, this politically sensitive project should too, presumably to highlight the pain of permitting. If a project with bipartisan consensus on its importance to national security cannot escape friction, what chance do other industries have?

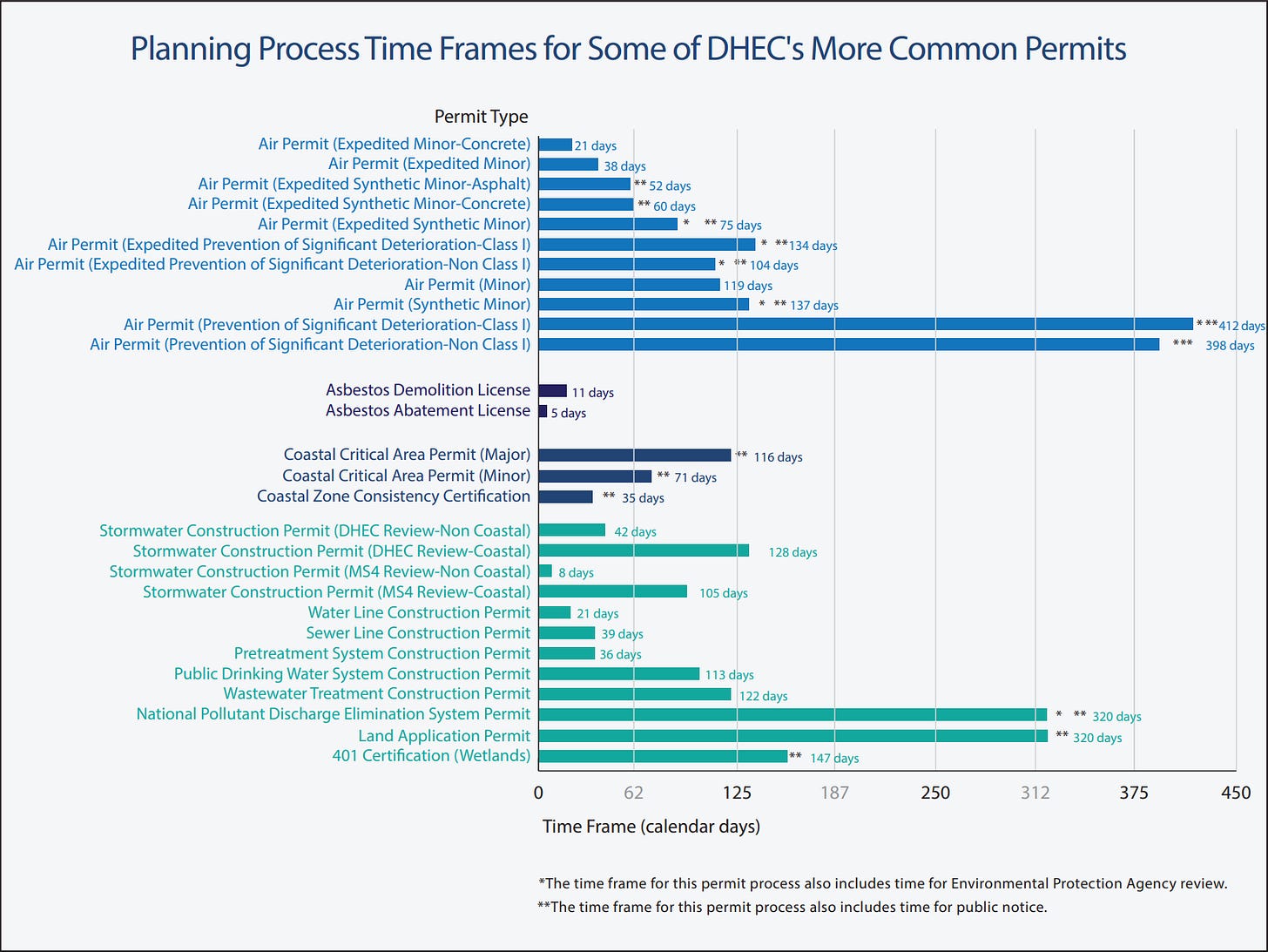

But the friction doesn’t stop at chips. Ben Reinhardt maintains a list that covers a wide range of examples. Within each industry, there are direct and indirect sources of friction. The direct sources include actual permits and regulations required by the federal and state government, such as environmental reviews, building permits, and air permits. These permits are not as simple as filling out a form and getting an instant yes or no. They take time. South Carolina has a blog post explaining their own typical duration to grant environmental permits and what factors influence their response time. Permits that only require local review range from 8-38 days. Permits requiring Environmental Protection Agency review and public notice periods start at 75 days and extend over a year to 412 days.

Indirect sources of friction would include things like roads, powerlines, waste management, water rights, and community attitudes. If they do not already exist, a new business must engage in a negotiation with the government at various levels. While most businesses do not encounter corruption, a significant amount of corruption happens through these negotiations because the government wields extensive power here, including the ability to indefinitely stall projects. Francis Fukuyama labeled the status quo as a vetocracy, a system of infinite interrupts that literally prevents progress without community agreement close to consensus.

As a result, building new industrial plants in the US requires significant conviction and buy-in from the various levels of government before committing financing. One cannot just build a new factory in compliance with the law, you need a personal relationship with the powers that be in order to operate your business. Little wonder why so much of American life feels politicized, because it is.

Progress in advanced industries like supersonic flight and nuclear reactors is simply barred. Congress passed a law banning supersonic flight over land, and the Nuclear Regulatory Commission approved ~2 new plants since the 1970s, a de facto ban on nuclear energy as a technology. Of course, researchers push forward on paper and attempt new designs overseas, but actually building things is a muscle that must be built with practice. When industry cannot attempt new things, they cannot learn and optimize the process, a phenomenon known as experience curve effects. This atrophy is visible in areas of national security, both defense production and semiconductor fabs. It is just the tip of the iceberg. The invisible parts are all the costs added to basic kinds of manufacturing in the US for everything from cardboard boxes to data centers. Even worse are all the projects that never make it past the drawing board because the costs and risks don’t calculate out. It is impossible to find that number, and the best evidence is simply how much manufacturing for the US is done internationally.

But it doesn’t have to be this way. To understand how to evolve, we first need to understand that friction exists for a reason.

The present system is a response to two big forces. First, powerful government officials like Robert Moses in New York City affected dramatic, controversial change in communities against their wishes. Second, industrial companies in the US caused significant harm to the environment, in some cases through indifference and others through ignorance (with big questions about what they knew and when). As a result, the modern system has little cost to halt development of any project for almost any reason as long as it is couched in environmental terms. These interruptions have an outsized effect on the interrupted, as it erases certainty of scheduling construction, making it take longer to make money, and increases costs to address legal challenges and costs of financing the project. Returning to the CHIPs Act, even now, the Sierra Club is mulling a challenge to stop new fab projects via an environmental review challenge.

A better process would synthesize these challenges into a system more conducive to growth.

Specific to the problems discussed, companies can and should bear costs for environmental damage. Previously, the US government successfully addressed worker’s safety by simply setting default liability for companies when workers were hurt on the job, including predetermined penalties. Why not build a similar system for damage to the environment? Companies respond forcefully when these externalities are imposed on them, as demonstrated by workers compensation.

Additionally, it seems impossible to move forward without improvements to state capacity. To be clear, state capacity is not about the size of government but the effectiveness of government. To start, state governments can implement legal frameworks that guarantee projects can move forward upon certification, likely a form of ministerial approval. Noah Smith explains ministerial approval as: “...you have a bunch of government workers examine the project and make sure it checks all the relevant regulatory boxes, and then if it does, you simply allow the project to go ahead, without lawsuits or multi-year studies.” You might be mistaken for thinking that is how it works today because it is eminently reasonable and, in fact, (again quoting Smith) “how Japan does things, which is why they’ve been able to build enough housing to keep rent affordable.” States could also add a service level agreement, a common feature in services businesses where the operation providing the service is required to fulfill their duties in a set amount of time. That typically carries penalties if they do not uphold their end of the deal. The states can and should compete to develop the best system. That system is in its infancy today, with states like Texas, Arizona, and Ohio actively competing for all kinds of manufacturing projects, especially semiconductors and clean energy projects.

There are almost certainly other kinds of federal, state, and municipal reforms possible to build a culture that allows material progress. The benefits of doing so are hard to understate. For one, erasing the cost and uncertainty of manufacturing projects will make more kinds of projects possible. Ideally, industrial companies would select to build in the US because it is the most globally competitive place to build, not because of subsidization. Two, the more we build, the better we will get at it. Three, these ecosystems can create positive feedback loops, with new kinds of companies and innovations possible, as seen in older hubs like Detroit and newer hubs like Shenzhen.

But more fundamentally, the vetocracy is an affront to a culture that values liberty and innovation. Even now, great policy wonks are at the vanguard leading the way, but they need both receptive ears in Congress and people to champion the cause in their own communities. Policy matters, but great policy is only possible with a great culture. Recognizing these issues and resolving them requires the US evolving, politically and culturally, and that must start with us. The community itself has to be pro-growth, it needs to set the agenda and find solutions that empower growth and protect the community better than the stasis produced by the expense and uncertainty of current processes. The problems are entirely of our own making, which means we have everything we need to fix them—if we have the will to do it.

Thanks to Rob Tracinski, Sarah Constantin, and Shreeda Segan for help with this post.

I’m always surprised when I come across someone who defends NEPA. Great piece.

Rob, thank you, I love your writing! Imagine where we would be in Software if they regulated bits as much as atoms. Sadly, we may soon find out thanks to SB 942...

When it comes to manufacturing, the US entrepreneur took it on the chin in so many ways. Only industries with unions were partially protected and then corporate suites boosted their pay with financial chicanery. Innovation in machinery and robotics in many industries essentially halted due to cheap imports derived from exploitative labor.

Overburdensome regulation is the cherry on top!